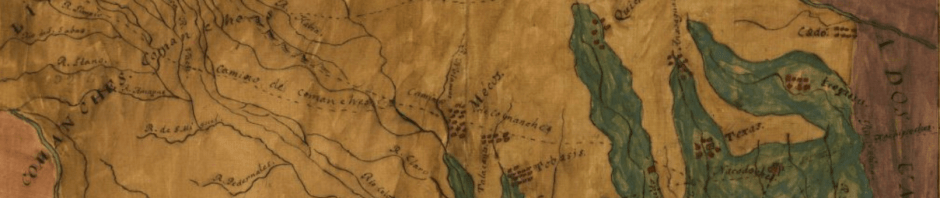

Map of Texas and its surroundings, attributed to Stephen F. Austin, 1822, Library of Congress.

This map, hosted by the Library of Congress (https://lccn.loc.gov/98687158), depicts Texas immediately after Mexico’s independence from the Spanish Empire. The map is attributed to Stephen F. Austin, the first of the empresarios (colonization administrators) whom the young Mexican state allowed to manage and profit from settlement in the tenuously held border region. Austin, cooperating with North Mexico’s existing socio-economic elites and later empresario’s, was hoping to establish a U.S. South-style cotton economy in Texas. This necessitated reshaping diverse local landscapes according top the logics of plantations and commercial agriculture.

The map shows Texas in beige and teal. The latter seems to indicate wooded river-bottoms, the former less timbered prairies, plains, and hill-country. Other Mexican districts are in pink; U.S. Louisiana is in purple. The Sabine River/Rio Sabina can be seen clearly along the U.S.-Mexico border, curving into the teal in the north and emptying into Sabine Lake in the South. Roads cross it twice, leading to Opelousas and Natchitoches out of Texas (and notably not to Pecan Point along the Red River). Austin marks several indigenous communities on the map, one on the Sabine. The spelling is, to me, all but incomprehensible, and the name does not really align with any group inhabiting the region at the time. But the position indicates that Austin is marking the Nadaco/Anadarko community, part of the larger Caddo political and cultural community that had inhabited the region for millennia. (Perhaps this is meant to indicate Cherokee newcomers who had begun settling in the region, but I doubt it.) Surrounding communities–Caddo/Cadó, (Hasinai) Texas, Quichies/Kichai, Alavanes/Alabamas (newcomers to the region), etc.–also extracted resources from river valley at that time or in the preceding decades. The Alabama and Cochates/Coushatta had lived on or near the Sabine a decade or so earlier.

The woodlands and unmarked prairies of the Sabine were zones of agriculture and the extraction of resources stewarded and extracted by indigenous communities, sometimes for market use (bear and deer hides, for example) but usually for localized subsistence. The Sabine Valley, not to mention the entirety of Texas and much of West Louisiana, is represented as an indigenous space. Nacogdohces, San Antonio de Bejar/Bexar, and La Bahia are tiny islands of Spanish-speaking settler society in a sea of diverse native cultures. This is a map of, to use Kathleen DuVal’s term, native ground. Simultaneously, this map represents a project to undermine that status through colonization.

EDIT: The incomprehensible labelling likely does not refer to the Nadaco Caddo, but to the Yowani Choctaw, often rendered as Iguanés or something similar in Spanish. These Choctaw had immigrated into the area in the mid-eighteenth century and assimilated into the Caddo cultural and political network. In contrast, later Choctaw immigrants to the region maintained independence, linking to hispanophone communities in the area. Most Yowani relocated into Indian Territory in the nineteenth century. Members of the Mount Tabor Indian Community, a controversial group operating primarily out of modern Rusk County, Texas, claim Iowan descent.